2 notes before the main event:

1)I don’t feel I can publish this essay at this time without saying: FREE PALESTINE, CEASEFIRE NOW, END THE GENOCIDE, LIBERATE THE PEOPLE AND LIBERATE THE LAND.

I wrote this text summer 2021; if I started it now it would be very different, and the center would shift. I also don’t think I have the attention span to write like this at this moment in my life/the world so I’m grateful to whatever spirit was flowing through me. I’ve added a few edits but otherwise it’s kept its original shape. Let’s go:

Clay AD

I’ve realized lately that one of my biggest turn-ons are people that will talk about god with me. My inner teenager who defiantly “quit” the church at 16 is like, ugh... dude this is very cringe. My inner elder just shrugs, accepting that this is who I’ve become, making space for my present self to admit how nice it is to get metaphysical with someone, and at the same time lazily contemplate how their dick would feel in my mouth.

In 2011, the artist and writer Johanna Hedva made a list I love called, ‘Everything Is Erotic Therefore Everything Is Exhausting’ It was a participatory performance that attempted to, in their words, “catalog everything erotic in the world, and which will never be complete.” Some that stand out to me:

I really enjoy the impossible task of naming them all. As I greedily go through the list, I begin to cross-reference, delighting in many of the visceral experiences Hedva draws the reader to. I relate to many, and through the language I can feel some of them in my body. However at some point I realize the catalog is missing a reference to one of my important epicenters of erotic experience: dance.

Dance, in an expansive idea of what that can be, has been and is one of the most erotic places for me. I mean erotic here in the lineage of Audre Lorde’s essay, Uses of Erotic: Erotic as Power, where she says:

Dance has taught me about energy, life force and movement. Dance became a church to me, one that I could go to any day of the week. A space to be alone and together. There’s a drama to this proclamation, and I declare it in full drama: I believe dance saved my life. A force which moves us towards living. Dance moved me toward recovery. However, dance isn’t a martyr on a hill. It’s simply there, and has been since humans have existed. It’s free, contagious and one of the means we have to communicate beyond language. It allowed me to consider that my body could be a home rather than a site of pain and disappointment. Dance became a shortcut to an awareness of god.

I don’t have a lot of clear memories from my youth. I’ve spoken a lot about it in therapy. The images are patchy and the emotions pretty much non-existent. I often cannot locate or remember how things felt most of the time. Eventually I named this – disassociation. Slowly, as I get older and deeper into my healing, moments come back, the onion of time unpeeling.

But I remember the sweaty body, tingling with contact edging on pain in the mosh pit.

Energized and a bit drunk in a church basement, moving to one of the many punk and hardcore bands that I followed like a dog on the trail of a scent. The joy, adrenalin, pot and cheap vodka an older friend bought with a fake ID swirling into something between a dance and a therapeutic tool, channeling a different life and a way of living which I could not yet know, but I felt shimmering in front of me. My nervous system heightened but responding with rage, despair, love, bliss, and peace amongst the upheaval. A joyful undoing and remaking of the body with the other bodies I was in contact with. A space to lose myself in a collective and dissolve. A container for the anger which I could not name but carried within me. My friends and I playfully beating each other up. I’d wake up with bruises and tell my mom I’d fallen at soccer practice. Finding myself in those scenes was a psychological relief; it all felt like a more honest reflection of life.

These temporary all ages show-spaces with their shitty PAs became my church, before and after I dropped out of the actual church at 16. And often, as I said, shows were literally in church basements around my mid-sized Midwestern city, as well as in more traditional venues, record shops, basements and cafes. Maybe that was an early noughties trend? I hope it still continues, the church providing a space that won’t be gentrified out of existence as many of the spaces that I used to go to have been.

Given the general lack of memory from my early years, the images of these shows and spaces are hilariously vivid. Drinking in the bathroom stalls with friends. The very satisfying and surreal sight of a singer screeching anti-establishment lyrics, often extremely anti-religious lyrics, in a drably painted canteen with a large framed printout photo of Jesus next to them. No gods, no masters. The church’s bulletin-board crowded with calendars of community activities and dates for the soup kitchen, placed alongside vacation bible school posters with Veggie Tales cartoons dressed in the clothes of biblical times (if you know, you know). Somehow these basements all looked the same: an interior of beige or pastel color textured wallpaper, with folding tables and brown or grey stackable chairs spread across a checkered linoleum floor. For a few upside-down hours the rooms would be cleared of the tables and chairs and swarmed with youth and the sprinkling of old timers in my city’s scene, dressed in black band t-shirts and looking strikingly unkempt against the 1970s-style sterile background.

It kept me going through the school week to look toward the next show. I could metabolize and accept the conditions of my life knowing that what felt like my actual life was waiting for me come the weekend. The shows would always be on Friday and Saturday nights, the basements cleared and cleaned for services on Sunday. Which in a way reflected a very Protestant relationship to the work week. There is the time for fun and then the time to be serious and they are definitely separate. No hoodies at church. Put on a dress.

I could express myself in a more aligned way in these spaces, my uniform of baggy clothes on my awkwardly tall frame of a “girl” in settled and unquestioned peace. I have an image that I hold very tenderly of the t-shirt I never changed out of my entire thirteenth year which read “Question Authority,” bought from Hot Topic with money I made from babysitting. Even when I played with femininity as an older teen, punk shows were a space where I could do it my way, rather than the dominant idea of what that was supposed to look like. I was not one of the cool or charismatic characters in my scene. I was very shy, searching for belonging as young people do, but I found a vast and lasting connection through the music. It became a healthier space for my obsessive brain to rest in, listening to a song over and over to memorize the lyrics. My friend and I burning one another CDs we would rip from the library or download. Dialing into my family’s internet for hours to read about bands, my family members yelling at me to get off so they could use the phone line.

In retrospect the conditions were far from perfect. The guy that ran the record label we followed religiously got called out for sexual violence a few years ago: he promptly shut down the label and moved to another state. As I was told what happened by an old friend, my stomach dropped, but my rational mind wasn’t that surprised as I mentally flipped through his dating history with much younger women and femmes. It made me sad as it tore apart the community around that label and its specific genre of folk punk. The scenes I moved through also were all incredibly white, and I know resulted in harm and discomfort for those who weren’t. The pit could get violent, depending on context or venue it could be very intimidating to mosh, especially for smaller people and women/femmes.

Ideals and opinions could be dogmatic, and some that have stuck with me have made certain forms of growth difficult as an adult. Here I also got my first taste of left wing movement spaces, which themselves can have a very Protestant approach to organizing and pleasure, often with little awareness of this tendency. There’s a pattern of deferring pleasure and glamorizing hard work for the sake of it, rather than attempting to enjoy this world while working for the next one.

As imperfect as it was, it was in this place that I was slowly politicized. Picking up ideas and building a new foundation of thought. Learning about anarchism through lyrics, zines and action. Learning about the genocide of the indigenous people of the land where I was born. How Turtle Island was colonized.

About the Spanish civil war. About how American taxes directly fund Israel‘s genocide of Palestinian people and the occupation of their land. That Fred Hampton was murdered by the US government back COINTELPRO.

That the war on Afghanistan was set up. The lyrics of anarcho punk and hardcore bands gave me a more honest history lesson than anyone was getting in my public school. In practical ways, outside the shows, I also experienced people helping one another out; Food Not Bombs and DIY fundraisers were some of the earliest examples of mutual aid I witnessed. It was a place where I experienced visibly queer sexuality and genders in my conservative state while I was still in the closet.

In reflection, all these ideas were precious but, for me, the embodied power of these spaces lay in the fact that it was a group of people that moved together. That in unison, the ritual of moshing and experiencing music through the body gave me a way into myself and a way out the norms I was expected to conform to, and this was positively reflected back to me in others doing the same thing. Or maybe that’s just how I’m narrativizing it now, looking backward in the recounting. Attempting to understand my formation through what Susan Stryker calls the “historicity of identity”, which she describes as the contingency of oneself in the context in which one becomes a self.

I cannot separate my becoming a self from dance. There are multiple formative chapters, but the self-awareness of the importance of dance didn’t arrive in my story until I was twenty-three years old. This is when I found my way to improvisational and contemporary dance classes and jams. It began during a burn-out, a friend dragging me along to a $5 community dance class held in an old church (the theme continues) because she could tell I was emotionally low and numb and needed some kind of positive input. It worked. I mean it didn’t cure whatever was going on with me, but I kept going. Finding a space for dance that was about expressing feeling, curiosity and desire awoke me to the possibility of a relationship to the body which was centered around sensation. I remember my first class, the teacher asking us to move from a strong impulse in the body, so I focused on my chest. As usual it was tight with anxiety and tension but, for the first time in my life, I approached this space in my body without frustration, but instead by asking it what it wanted. I tentatively listened and began to move.

This moment was shaping. It began to teach me the lesson that I didn’t have to have a punitive relationship with myself, that I could at least be curious. It gave me another option to encounter pain and tension: sit with it and listen, rather than avoid and distract or control. As I dove deeper into dance and somatics throughout my twenties, I encountered various body nerds and dance geeks and movement witches and trained freaks and improvisers who offered countless thoughts and alternative approaches towards this thing we call body, self and mind, or the soma.

It opened up and changed my world completely.

During this time a teacher and fellow movement witch, Maria F. Scaroni, introduced us to a practice of hers to use repetition as a technology of ecstasy. She invited us to shake for a long time, maybe an hour or so. I can’t fully remember, but it felt like a long time. That experience brought me to a feeling of interconnectedness in the body, like my edges were buzzing and dissolving. I found the sensation spiritual as it revealed a truth of my beings’ relationality to the others in the room, the city, and the planet, through a feeling in the body. I left my head -- it was a truth-thought felt throughout my being. I realized later that it was a very familiar state to me. It was one I had had many times before in the mosh pit, which now I can see was my first encounter with what could be called the ecstatic through movement.

Throughout nearly all of recorded human life on earth, certain forms and rituals around dance have functioned to be ecstatic in nature, resulting in states of trance and heightened emotions. From paintings made during the Stone Age depicting dancing, to the mosh pit or contemporary club, dance has been used because it is a powerful technology, a means of feeling god(s) or spiritual experience or connection to the collective through the body, rather than only believing in its power with the mind. Ancient Greeks would partake in worship of Dionysus, the god of wine, in which female followers would seek a state of “ekstasis” which means “to get out of themselves,” through wild collective dance. They were trying to achieve a state of possession by the god. Sufi whirling in the 12th century was used, and is still practiced today, as a moving meditation to connect to Allah through symbolic imitation of planets revolving around the sun, resulting in trance-like states. In Santería, an African diasporic tradition which developed in Cuba in the 19th century, dance and drumming are used as an invitation for oricha, Yoruba deities, to possess and thus communicate with members of the group. For many queer people dancing amongst one another, whether in the club, a house, a squat, a bar or a field has been a place of ecstatic experience and becoming in a world that is hostile to our joy.

These examples are just a drop of water in the ocean of the varied ways humans have engaged and cultivated movement technology for culture and worship, as well as individual and collective understanding and connection. I began to get curious about the histories and lineages of dance as a means of spiritual experience, particularly in the lineages I am directly connected to, i.e. my various European ancestral descendants. In my search, I quickly realized, without much surprise, it would be a story of religious and state repression, using discipline as a means to curtail ecstatic expression’s transformational force. This repression took place through colonization, the stealing of land and culture from others, as well as being aimed at cutting off their own polytheistic roots. As well as exposing the strange paradox that is at the heart of Chrisitanity: a belief in the embodied and incarnate God – a God who becomes flesh through the birth of Christ – and the fact that the contemporary institution of Christianity instead promotes disembodiment and disincarnation.

Its necessary to state before we get too deep into it that I’m attempting to find the stories of Christian religious history which has led to shaping me. There are infinite contemporary expressions of Christianity around the world I have not experienced, many born out of violent colonial histories of forced conversion, the fugitive mixing of gods and practice, long standing Christian mysticism and/or the lasting impacts of early heretical movements, which have developed and held onto traditions of ecstatic expressions of song, dance and movement in worship. I want to demarcate this because, at least from the outside looking in, they’ve maintained a connection to aliveness that was not present in my experience.

Looking back is an attempt for me to understand where the sense of aliveness went

. That question of why comes from memories my body holds. At a young age I remember getting in trouble from a friend's mom for wiggling to the sound of the choir music in my seat. Sit still, she hissed and held me down painfully. I felt immediate shame and fear. The churches I went to as a young person were racially diverse, however in retrospect the dominant culture was a strong belief in respectability, individuality and middle class values. The stone building sits heavy in my mind with how white supremacist culture created an ethos of the body being locked to the chair while a minister stood up front speaking of the power of God to move mountains.

In Barbra Ehrenreich’s book Dancing in the Streets: a History of Collective Joy she gives a thorough and nuanced outline of the church’s relationship to ecstatic movement practice. I want us to move together, so I will attempt to summarize here what stood out to me about early Christianity and dance so we can stay connected.

A Short and Dirty History of Christianity and Dance

At its roots Christianity included dance in worship. Clement of Alexandria (150-216CE) told followers in an early Christian cult to dance initiation rites in rings around the altar. Early Christianity was built on collective life – eating with one another in groups and participating in ecstatic rituals, like dance or speaking in tongues. Jesus’s radical origin story as an anarchist figure preaching love and sharing was a ministry that attracted the marginalized, women, the poor, sexworkers and the sick. Once the Romans took over and adopted Christianity as the state religion, it became more regulated and given increasing hierarchical formality and the marginalized were again pushed out to the edges.

However, into the Middle Ages, churches still danced. Priests and archbishops were even known to join in the holiday dancing within the church building itself

, or in the graveyard, a practice harkening back to paganism. Many churches were originally erected on holy pagan sites throughout Europe as a strategy to convert followers, so on these grounds ritual dancing was embedded into the soil, and was remembered through the body, repeated in an echo of its previous life. On the other side of the coin, dance outside of the church during the Inquisition

saw collective movement and celebration as potential signs of witchcraft – believed to be instigated by Satan himself – whose portrayal looked strikingly like the pagan god of revelry and drinking, Pan. Those accused of participating were often executed, imprisoned or tortured.

Dancing within the church and graveyard stopped in the 12th and 13th centuries when priests began to purge dance physically from within the church, relegating it to specific holidays, both secular and holy, for example carnival. This was a compromise to dissuade heretical movements from springing up in response to an outright ban on celebration which, of course, failed, as heretical movements still formed despite their efforts. The church wanted a monopoly over human access to the divine, not only as a means of controlling Christianity’s narrative, but also safeguarding the church’s increasing wealth and political power.

Carnival existed as a means of revelry and, I’m sure, a space of ecstatic experience, whether through dance or substance. This festivity would harken back to pagan ritual, and also be used as what Ehrenreich calls a “safety valve,” for the powers that be. A day a year where the elites would allow ordinary people a space and time to let loose, to burn political effigies, to play and to dance.

However, from the 16th through 19th centuries, state and church attempted to control, sanitize and shut down carnival, typically by not renewing the permit to host it. These bureaucratic controls leaked out onto saints’ days, holidays and other occasions for reverie and play. In the south of Europe, spaces of carnival have continued, some becoming more of a procession ritual and others holding fast to their original wildness.

This repression of carnival is intimately tied with the dissolution and loss of the commons for the people and the spatial segregation of class in urban space. It wasn’t only the church that feared carnival, the state was also in favor of sanitizing or exterminating it. One reason for this antagonism was that, in the 15th and 16th centuries, carnival began to be used as a distraction for rebellion, robbery (think Robin Hood) and challenges to the powers that be. Everyone was conveniently wearing masks and costumes anyway, thus it was the perfect concealment. The aesthetics and rituals of carnival leaking into radical politics can also be seen in larger revolts such as the French Revolution, when animals were dressed up as politicians, and people made music and danced in the streets.

With the rise of displaced peasants and the growing underclass in cities, tensions across Europe were extremely high, so spaces of celebration, togetherness and debauchery were regulated. In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, the elite disappeared into their own parallel festivities of excess and wealth, the medieval practice of common celebration severed: let them eat cake.

When the Reformation happened and Protestantism arrived on the scene in the 16th century, dance, and collective celebration in general, would be under further threat. Lutheranism and Calvinism, the early strains of Protestantism, disdained excess, celebration, drinking, gambling, and dance. They were seen as sin and a distraction from God. Politically, Protestant foundations of thought supported many ideals central to the emergence of capitalism. The middle-classes learned to calculate, save and defer gratification and the lower classes were disciplined into factory work six days a week. Ehrenreich makes the really interesting point that:

Scientific and philosophical theory of the time followed in the church’s footsteps to create a well rounded culture pitted against embodiment. Religious oppression of dance coincided with 17th century Age of Enlightenment attitudes towards the body, relegating it to a machine that was in service to the mind.

Seeing folk dance across cultures keeps me rooted knowing that spirit has stayed, regardless if it has been severed from the spiritual by oppressive power. I think about the contra-dances I grew up going to, and now the ceilidhs I’ve attended in the last three years living in Scotland. I’ve been grateful to experience the collective joy that erupts in these community dances, which I can feel through my body harkens back to something ancient, land based and important; even if that’s simply the connection of sweating together in unison on a cold winter night to experience being alive.

What I can tell from looking into all of this is that through the rise of state power and control of the Catholic and then Protestant church, dance in much of Europe was mitigated to being viewed as purely sociocultural, or given specific steps and technique and then raised to a “high” art form. It also became clear that the secularization of dance is also a story about class. Courts began to use dance as entertainment, developing concert dance such as ballet in the 15th century. While there is nothing wrong with form and training, I’m curious as to whether it lessens the availability of reaching ecstatic states, as a necessary part of the experience is the loss of control, which helps to move awareness from the mind into the body. Or this is how I’ve felt its power. Maybe it’s simply intentionality and the knowing, whether from self-experience or teachings or cultural context, that it’s possible to spiritually connect through dance. I know it can happen for individuals in folk dances, and even ballet, just as it does for some in the club, as almost anything can be devotional if there is intention behind it, but the relegation of dance into the purely social, and purely secular, is a site of mourning for me. So I ask, digging into what might have been and still could be:

Though I don’t know what was lost, I do know where some rigidity was cultivated in its wake. My great grandmother was an active member in the German Mennonite Brethren Church, which originated in Germany, and whose congregation emigrated to the states due to religious persecution in 1719. My grandmother and mother speak very highly of her kindness, and I was named after her when I was born. Although she died when I was six and it’s a name I don’t use anymore, I still feel some kind of intimate connection to her. She was the child of German immigrants who arrived in Louisville, Kentucky in the early 20th century. Her family attended the church there as the service was held in German and her parents didn’t speak English. It was a fairly strict denomination of Protestant Christianity: there was an abstinence framework and they were not allowed to gamble, drink or dance, much like Calvinism’s original doctrine. My grandmother did not raise my mother in that church, nor her with me. I was raised in two different Protestant churches during my youth, and was actively engaged in those communities until I decided to stop going as a teenager.

I think about this generational relation to restriction through Protestantism and compare it to my mother’s father’s side of the family that has historically (and presently) struggled with addiction, with many relatives dying from alcohol-related illnesses. Restriction on one side and excess on the other matriarchally. This pendulum of being would become my way of coping, swinging between control and chaos, excess and restriction, lost to myself in this whiplash until my late twenties. Operating under a functional facade while being scared of almost everything, especially my own emotions.

It's important to mention here that my first expression of restriction came in the form of a childhood eating disorder which continued in different forms until three years ago when I sought recovery. It began when I was quite young. Food was there as a means to control my emotional states, a way to numb myself. It was the only tool for emotional regulation I had access to as a young person. Now I can see that with compassion, but until very recently it was a huge source of shame in my life and something I kept hidden, even from those I was in close relation to. When I think about it, this logic of rigidity fits well within the conception of a judgemental God.

In attempting to relate to my great-grandmother, I try to imagine life with the religious restrictions she accepted. I have been sober from alcohol for a while now, which has been hugely beneficial to my life, and I don’t gamble, so in these particular ways I can relate to her existence on a daily level. But I can’t imagine a life without dancing. Even when I’ve been in bed, sick as a dog with a flare-up of my chronic illness, I still, even in the most subtle ways, moved. I find joy watching others dance. I dance often in my mind when I’m bored, imagining what I’d like my body to do, how I’d move to a particular sound, what movement the music evokes and calls the body to make.

When I think about that impulse to dance being seen and metabolized as sin I get unbelievably sad. I think about that being carried generationally in the body through my matriarchal line, and what it means, especially in my body of white settler lineage born on colonized land.

Ritual dance, or even dance for pleasure and fun, was a threat to Protestant ideals because it brings you in contact with desire, possibly even with Lorde’s concept of the erotic. It can potentially bring you to the awareness that you are the body, and that the body is not divisible matter from the mind or the spirit.

My own self-made church of rigidity began to crumble when I could no longer be in the delusion that I could control my body. The image I have of this moment is a hand cutting a string, a clean “before” and “after”, my world suddenly very changed. At sixteen, after a year of mysterious symptoms and pain, I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. It took about eleven more years to find recovery from my eating disorder, but somehow, still, I think of diagnosis as an “oh shit” moment where the forms of control I had been playing with broke. I still played with them for a long time after this, but they didn’t work anymore like they used to, and I mourned this. I mourned that obsessive rigidity could not give me a pure high anymore, it was tainted with the fear that I would make myself ill. Strangely, this was a thought I never had before I actually started getting sick, even though eating disorders are dangerous and can be deadly. Sometimes I didn’t care about this fact and would engage in destructive habits, welcoming the breakdown. But because I knew there would potentially be a breakdown, I couldn’t live in my conception that the rigidity would save me from my life falling apart. That it would lead me towards some kind of perfection. It was all a big paradox. However, here I see the Protestant root. That perfection is achievable, that heaven, something beyond this earth, is the end goal. That a totally different body, and also personality, beyond my flesh and blood and experiences, was my end goal. I can make this connection now but back then my mind was constantly circling around something which was always out of reach.

It’s strange to alchemize these drives in writing, but I imagine it's a relatable state for many, as being young is often confusing and painful, even under ideal conditions. I was a lost teenager without any tools. I wouldn’t come out as trans until ten or so years later, but I definitely had a complex relationship to my gender, sometimes consciously expressed, but mostly unconsciously. Everything was a paradox. I was obsessive. I wanted attention. I wanted no one to look at me. I wanted to completely control my body and, at the same time, I didn’t want the burden of one.

Thankfully, I’m in a very different place now. Recovery for me has not only been about recovering myself, it has also been an on-going (and never ending) attempt to dig into the soil and detritus of what vitality and joy was lost, strangled and stamped out of my lineage, from both perpetuating harm and surviving it. To reconnect and love my inner child and teenager. I have tried to connect to those around me, facing similar struggles, to ask the question, not only to myself and those around me, but also to my long gone kin:

and

Rigidity does not stand in connection. We have to bend and move to be with others, All that you touch you change. All that you change changes you. The only lasting truth is change. God is change. So insists the prophetic texts of the religious cult in Octavia Butler’s seminal speculative fiction Parable of the Sower. This conception of god resonates with me, I see it as a living example all around me, all the time in macro and micro ways. I see it in myself, in the humans and non-humans living beside me. I even see it in the mosh pit.

In the pit, the band needs the crowd and the crowd needs the band. They both need and feed off of that connection. It’s a feedback loop that obviously frays at times but generally, at least in my experience, both elements are in service to each other, to something larger than themselves.

In his 1962 essay, ‘The Decline of the Choral Dance’, Paul Halmos described the decline of choral dance, which is any kind dance done in unison as a group, in favor of the rise of the pair dance, or couples dance, such as the waltz or swing. In his text he is speaking about folk dance done by people, not performers, which is passed down culturally. Aside from offering a kind of critique of the nuclear family and heterosexuality, the essay goes into ideas about humans’ group-drives and biosocial needs. Halmos states that, through choral dance, people would achieve two objectives:

Moshing, a kind of contemporary choral dance, was a primitive therapy for me, and knowing many kids in those scenes at the time, I assume for them as well. My mind immediately going to friends, mostly angry, beautiful, chaotic boys, who would work things out in those spaces, and complicate some of the specific troubles the normative masculinity that was being forced onto them. It was a [safer] space

to express anger and violence potentially without intentional harm. A kind of peer DIY Gestalt therapy

, but instead of hitting pillows we were (consensually) hitting each other. I learned there that dancing and moving together, whether in spiritual communion or or not, can be healing for the group and the individual.

The theory of Interpersonal Neurobiology, also known as relational neuroscience, supports this idea: it describes human development and functioning on the neurological level as a product of the relationship between the body, mind and relationships. Basically, it means that our entire nervous system, including the brain, is never an independently formed thing, giving legitimacy to the idea – probably pretty obvious to most – that we are organisms in relation, shaped in relation, changing and responding to our environment and those around us. However, neoliberalism and capitalism try to tell a different story of personal change, through individual willpower and work within the system as it stands. I’m curious to find communities that move together – through political organizing as well as physical movement, play, dance etc. – and seeing what that movement creates and changes, as well as how it can confront the dominant forms of power. In searching for this, I found an 18th century Christian heretical sect called the Shakers.

The Shakers’ name denotes their primary act of worship: shaking. They would shake their bodies together in a large room to connect to god, shake off feelings of lust, and create a sense of unity with the group. The word Shaker originally was a slur that they then appropriated and called themselves. They believed God moved them, so, in worship, they made space to move. Early accounts stated they would spend entire nights in revels dancing with “hardly any clothes on” (potentially due to the heat of dancing all night, but who knows!) Later, the Shakers formalized worship, creating steps and formations for their movement. They’d call their dancing “laboring,” as it was work they were doing on behalf of God. During the service, some would beat time with their forearms parallel to the floor, palms facing down.

My first encounter with the Shakers was while visiting my childhood best friend in 2016. We grew up going to punk shows together, so she’s been quietly present within this writing the whole time

. She had just moved to a farm she ended up working at for six years in New Lebanon, New York. According to the 2016 census, the town has a population of 2,200 people. It was the main spiritual home of the Shakers, or ‘The United Society of Believers in the Second Coming of Christ’, and in 1864 there was a population of 609. They were a religious off-shoot of the Quakers from Manchester, England, who in 1774 came to the US led by an illiterate factory worker named Ann Lee, later known as Mother Ann by her followers. She arrived with eight others and moved to Niskayuna, the ancestral homelands of the Mohican, a tribe which was forced out of this area of New York because of the stealing of land and forced removal around 1810.

Mother Ann was guided by divine visions and signs which she received while in prison for religious persecution in England, which told her that she represented the female aspect of God’s dual nature, and that she was tasked to rebuild society in a different way. The Shakers were millennialists, which meant they believed Christ had come again, first in the form of Mother Ann and subsequently “in all in whom the Christ consciousness awakens.”

The Shakers are fucking fascinating. They are full of paradox, in some ways relatable and in others totally unrelatable. The drives of much of their sect/cult were directed by both asceticism and pleasure, simplicity and extremity. Their beliefs grew from Protestant roots, but somehow became open to the body through their faith practices, such as movement, as well as building and drawing. These practices allowed the individual to have a personal relationship to God. In this approach, they differed from more mainstream Christianity, where communication with God was filtered through the ministers, priests and biblical texts. As a group they were celibate, thus, no one could be born a Shaker, you had to convert. Converting meant turning over their lives and lifestyles, and agreeing to live within community; a covenant was signed confessing their sins, agreeing to communalize their wealth and vowing celibacy. During the height of their membership in 1840, more than six thousand believers lived in nineteen communal villages, from New England to Ohio and Kentucky. They believed that since Christ had come again, this world itself was heavenly and it was their duty to live in a way that honored that divine state.

Under Mother Ann’s direction, the Shakers attempted to practice social, sexual, economic, and spiritual equality for all members, because they believed Christ lived within everyone’s body. This was pretty radical for Protestant Christianity at the time, as it created a doctrine of spiritual non-hierarchy among all those who converted and lived in the faith. Gender equality was instituted within the Shakers in 1781, men and women both held leadership positions and, though the celibacy rule was spiritual, it also served a functional purpose in that it created a form of equality outside of the norms of marriage that governed gender roles at the time. Shakers were active members of the Underground Railroad, assisting enslaved people. Many believed slavery was evil and not within the law of God; their communities were an easy place to hide as they didn’t allow outside visitors. Those who escaped slavery, poor people and women would choose to join the Shakers as they offered a peaceful collective life where they could get their needs met, become members as well as leaders of the community, and be treated with respect and dignity. They also took in orphans from the state to raise.

They were into hard work – very Protestant – but also into beauty, function, and experimentation. Their communities lived off the crafts and goods they would produce and sell to the “Outside” world, as they called it. Their furniture designs are famous but they also produced many inventions such as the automatic spring, the turbine water wheel, the circular saw, the clothespin and packaged seeds, and were the largest producer of medicinal herbs in the US, amongst many other offerings. They didn’t patent their findings, but shared them freely outside their communities.

When I was visiting my friend, what really struck me was being surrounded by architecture that was built for community, with purpose and beauty in mind. These clumps of buildings would be called “Families”, which would house from 50 to 150 people. They called one another brother, sister, elder and eldress. In New Lebanon, the old Shaker buildings now house a boarding school and a Sufi spiritual commune which moved in in the 1970s. It also had a past life as a communist children’s camp. I’ve spent a lot of time living in or actively visiting collective spaces throughout my life, and the stories I heard about these people sounded so… queer to me, rooted in a conception of family through relationships rather than reproduction, and finding life outside of the mainstream norm of the time. Here I feel I need to say, it was just a bunch of humans doing a weird thing together, so obviously there were issues, but I want to honor the fact that these people were wildly strange, wise and graceful for their time. They were also settlers on stolen land. I’m also sure lots of complicated stuff went down within their communities as is normal in collective life, such as conflict, power imbalances and strain. They conducted a utopian experiment that has lasted two hundred and fifty years, which for some humans doing a weird thing together is pretty amazing, as many collectives struggle to function for a fraction of that time. There are presently two remaining members of the Shakers living in the last community in Maine.

I was still left with the question of why shaking? Being a bodyworker I know that physiologically mammals are wired to shake to release adrenaline and cortisol built up in the body after it enters fight/flight/freeze.

If you watch a video of an animal, say a deer, escaping a predator, when they’ve gotten to safety they will tremble. Shaking signals to the system that they are okay, that they escaped danger. After the hormones and energies have discharged they will move on, grazing as if nothing happened. The endpoint of this situation is called resolve.

Much trauma theory and neurobiology is drawn from similar examples, looking towards non-humans in the wild. These examples help us to understand our own human responses to real and perceived danger, in relation to what is happening on a neurological level in the brain and body.

Physiologically we respond quite similarly to the deer, however, because human brains, nervous systems and social contexts are more complex – for example, we developed the prefrontal cortex which allows rational thought and reasoning – the cycle is usually not so simple. We can also see this in adopted and rescued domestic and feral animals who have been traumatized, and whose responses don’t fit into the clean chronology of events described above. Because of the contexts and cultures we live in, there are also many situations in which resolve is not possible, nor discharge to achieve safety.

Even on a more basic level, many of us have learned as adults, in the context I’m from at least, to suppress our bodies’ modes of coping. We conform to social codes on how to act (i.e. it’s embarrassing to cry in public, don’t be too loud, don’t move or speak in ways that will confuse people or you’ll get called crazy) and thus, the hormones in the body are not discharged. When the body does not or cannot express itself after particular experiences, we shut down, metabolize this energy and store it. Sometimes, depending on the situation, this can become trauma, especially if, within that experience, we didn’t experience autonomy and/or safe connection afterwards.

Thus, in the somatics and embodiment world, shaking, amongst many other therapeutic practices such as breathwork, movement, somatic experiencing, laughing, crying etc, has become a popular form of release, such as in the practice of TRE (Trauma Release Exercises). This work induces tremors within the body by holding certain postures to micro-stress specific muscle groups, and can help release muscular patterns of stress, tension and trauma. The tremors are often working with the psoas muscle, which is active during fight/flight/freeze and provides core stability in the body, and when released can create quite profound emotional and physical sensations.

In the somatic work I do with clients I’ve seen many go into small moments of tremor or large expressions of shaking as we explore a physical sensation or particular memory. To allow these movements to happen and then change is to allow the nervous system to go through an expression, or regulation

, which I understand through Susan Aposhyan. As the founder of a somatic therapy technique called Body Mind Psychotherapy describes in her book, Body Mind Psychotherapy: Principles, Techniques and Practical Applications, the movement of an individual away from a trauma response through what she calls sequencing:

When thinking about the idea of sequencing I find myself asking the question:

Trauma does not exist only on the individual level. Lisa Fannen, a friend and the author of Warp and Weft: psycho-emotional health, politics and experience, re-frames trauma to broaden it from an individual problem, which the Industrial Wellness Complex

profits from, to a collective concern. She calls for us to question, or even dismantle, the structures and institutions which traumatize all beings and the planet in the first place, so we can move towards collective healing. She defines types of trauma not only as individual experiences, but systemic ones – ie. trauma from the state, institutions, oppression etc. I found this an incredibly useful articulation because trauma has been framed in the Global North in relation to mental health often as an individual problem even when the trauma occurs because of systemic, institutional or state violence. Fannen gets us to ask, if we’re not broken but the systems that have gotten us to this point are, what are the structures that could hold our healing and how do we find those together through practice? It makes me think of Christianity’s origins, the Jesus that welcomed those of us on the edge to spend time together to experience the divine, rather than the common experience of Chrisitanity in the last years that demonizes those struggling to fit in the norm and further alienate and persecute them.

That said, I think finding release on the individual level is also imperative for collective freedom, and therapeutic methods and tools from within the embodiment and wellness world can be transformative. I have experienced this myself. However, I think it needs to be both, inseparable and spiralic. I think personal healing flows outward and allows connection and trust, and connection and trust with beings outside of ourselves can invite us into individual healing. However, by only pursuing individualized healing it is not an honest reflection of the crisis facing humans on the physical and spiritual plane that creates feelings of painful separation from self and world, self and community, self and culture, self and self, and effecting some more than others drastically depending on privilege, position and context. I think that’s why I’m drawn to exploring the ecstatic in the group in the past and present, whether through moshing or worship, because it challenges the capitalist neoliberal conception of healing ourselves to fit ourselves back into the normative world, to be a better, more productive worker, spouse or reproducer. Or the Christian version, to clean ourselves of sin to fit in and get in line for heaven. The ecstatic experience isn’t productive or based on specific morals and, in the way I’ve experienced it at least, clarifies the stakes that everything needs to change to reflect [my personal belief] that god lives through all of us and life is sacred. That means personally changing many conceptions I have learned or been given about the world. It also means changing how I connect and be with others to reflect and try to live this belief the best I can one day at a time.

I had the intention to do a shake every day while writing this text. Though it did not happen every day, I did shake most days, alone in my house or in the park, and from these shakes the structure and thinking of this text emerged. I don’t know if this experiment in shaking to catalyze the writing shifted or interacted with the vast amount of memories, experiences, emotions and trauma I’m holding in the body, but I do know that after I shake for more than five minutes, I feel more aware of my edges. I feel my skin buzzing. I feel more alive. Shaking puts you in intimate relation to gravity, the perfect amount of force which anchors us to the planet. I get realizations, urges and epiphanies while moving – I always have. The intelligence of my entire being is more active while in movement, even the smallest of movements, than when I’m, say, sitting typing at a computer like now. The shaking experiment was imperative to facilitating the muddling through of ideas, to allow the language to come first and foremost from the body, peppered by facts and reading, but at the core, held in a state of being. This is the state where I find a wordless answer to my original question.

In shaking, I experience the interplay and space between control and letting go. I start by bouncing my feet against the ground. Connecting to gravity through feeling myself falling, and the body catching that movement, the momentum bringing it back. The bouncing increasing as I try to release my limbs, let my arms flop around, shoulders slump, and my head roll forward. It offers a simple but profound lesson through experience. I wonder if that is what drew me to get in the mosh pit itself. Perhaps I could feel intuitively that it held this lesson for me, which I’d find words for later, but right then, it was simply the desire to feel another body slam against my own, to let go and to move together. To help one another reify our physical realness, clarify the stakes of being alive together, and to feel, harkening again to Lorde, a force which moves us toward living in a fundamental way.

1)I don’t feel I can publish this essay at this time without saying: FREE PALESTINE, CEASEFIRE NOW, END THE GENOCIDE, LIBERATE THE PEOPLE AND LIBERATE THE LAND.

I wrote this text summer 2021; if I started it now it would be very different, and the center would shift. I also don’t think I have the attention span to write like this at this moment in my life/the world so I’m grateful to whatever spirit was flowing through me. I’ve added a few edits but otherwise it’s kept its original shape. Let’s go:

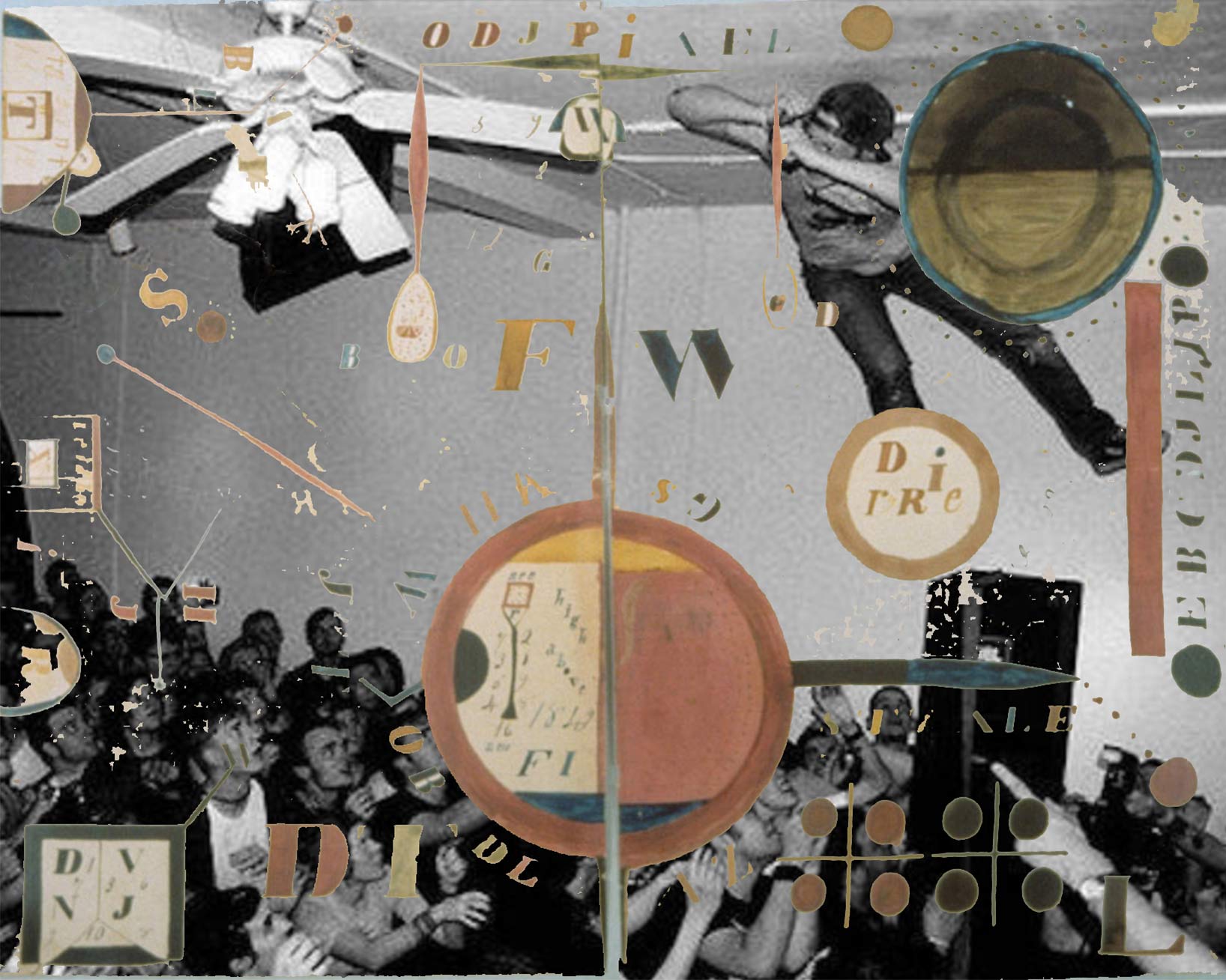

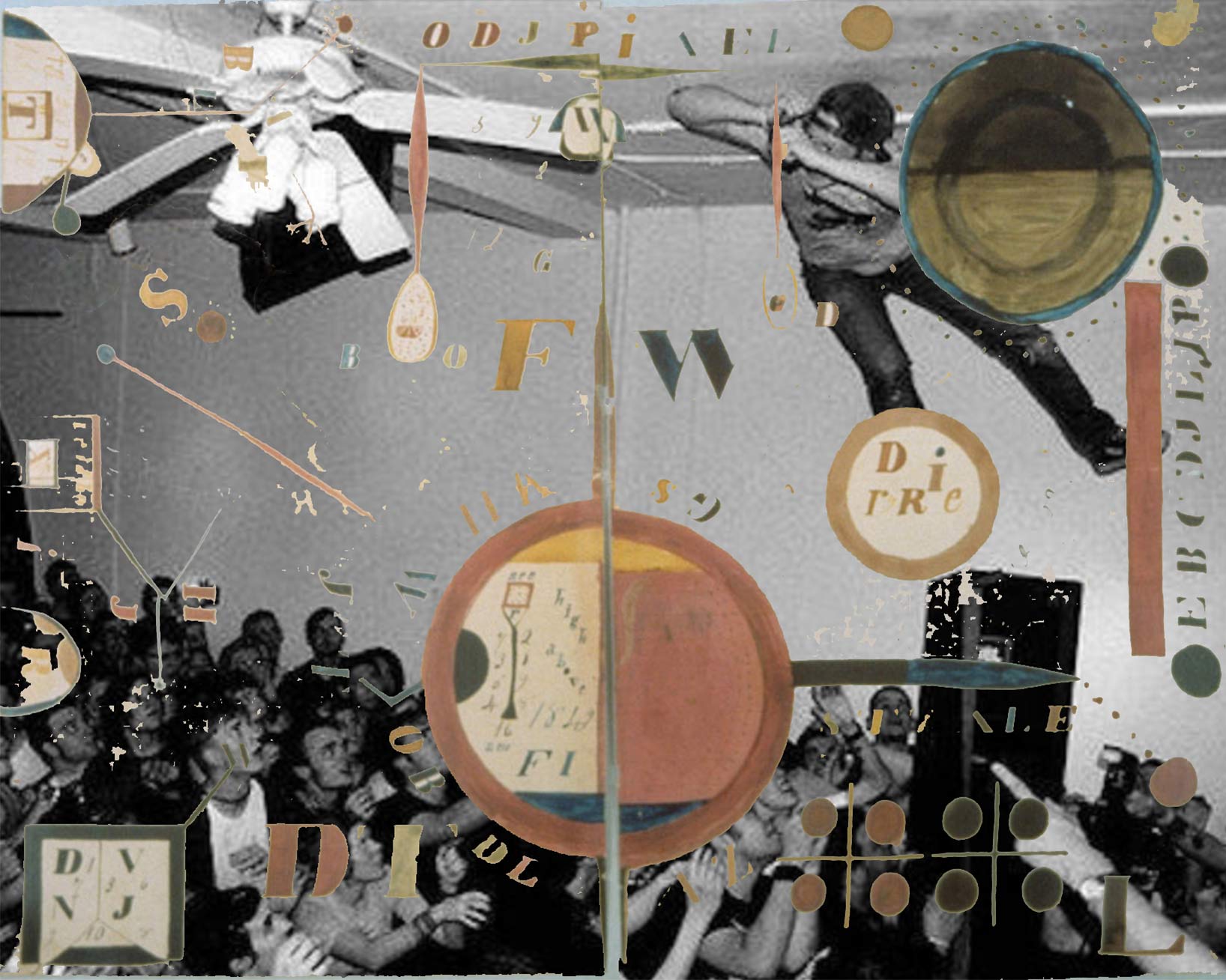

Collage by Clay AD, found image of moshing layered with Shaker Gift drawing, which were anonymous drawings made during contact with God. This one is from around 1840.

Clay AD

'Tis the gift to be simple, 'tis the gift to be free

'Tis the gift to come down where we ought to be,

And when we find ourselves in the place just right,

'Twill be in the valley of love and delight.

When true simplicity is gained,

To bow and to bend we shan't be ashamed;

to turn, turn, will be my delight.

Till by turning, turning we come round right.

– Lyrics from the hymn "Simple Gifts", generally attributed to Elder Joseph Brackett; composed 1848

'Tis the gift to come down where we ought to be,

And when we find ourselves in the place just right,

'Twill be in the valley of love and delight.

When true simplicity is gained,

To bow and to bend we shan't be ashamed;

to turn, turn, will be my delight.

Till by turning, turning we come round right.

– Lyrics from the hymn "Simple Gifts", generally attributed to Elder Joseph Brackett; composed 1848

I’ve realized lately that one of my biggest turn-ons are people that will talk about god with me. My inner teenager who defiantly “quit” the church at 16 is like, ugh... dude this is very cringe. My inner elder just shrugs, accepting that this is who I’ve become, making space for my present self to admit how nice it is to get metaphysical with someone, and at the same time lazily contemplate how their dick would feel in my mouth.

In 2011, the artist and writer Johanna Hedva made a list I love called, ‘Everything Is Erotic Therefore Everything Is Exhausting’ It was a participatory performance that attempted to, in their words, “catalog everything erotic in the world, and which will never be complete.” Some that stand out to me:

The act of, the sound of, spanking.

Any kind of slow dripping, like water from a faucet and honey from a spoon.

Balloon knots.

Being read to.

Being spit on.

Black holes.

The bulbs of irises.

Many tiny fish.

Any kind of slow dripping, like water from a faucet and honey from a spoon.

Balloon knots.

Being read to.

Being spit on.

Black holes.

The bulbs of irises.

Many tiny fish.

I really enjoy the impossible task of naming them all. As I greedily go through the list, I begin to cross-reference, delighting in many of the visceral experiences Hedva draws the reader to. I relate to many, and through the language I can feel some of them in my body. However at some point I realize the catalog is missing a reference to one of my important epicenters of erotic experience: dance.

Dance, in an expansive idea of what that can be, has been and is one of the most erotic places for me. I mean erotic here in the lineage of Audre Lorde’s essay, Uses of Erotic: Erotic as Power, where she says:

We tend to think of the erotic as an easy, tantalizing sexual arousal. I speak of the erotic as the deepest life force, a force which moves us toward living in a fundamental way.

Dance has taught me about energy, life force and movement. Dance became a church to me, one that I could go to any day of the week. A space to be alone and together. There’s a drama to this proclamation, and I declare it in full drama: I believe dance saved my life. A force which moves us towards living. Dance moved me toward recovery. However, dance isn’t a martyr on a hill. It’s simply there, and has been since humans have existed. It’s free, contagious and one of the means we have to communicate beyond language. It allowed me to consider that my body could be a home rather than a site of pain and disappointment. Dance became a shortcut to an awareness of god.

I don’t have a lot of clear memories from my youth. I’ve spoken a lot about it in therapy. The images are patchy and the emotions pretty much non-existent. I often cannot locate or remember how things felt most of the time. Eventually I named this – disassociation. Slowly, as I get older and deeper into my healing, moments come back, the onion of time unpeeling.

But I remember the sweaty body, tingling with contact edging on pain in the mosh pit.

1

Just so we’re all on the same page: the mosh pit is the area in front of a stage where moshing, pogoing or slam dancing takes place. These forms of dancing evolved out of punk, the term “moshing” itself is attributed to H.R. of the Washington, DC hardcore punk pioneers Bad Brains. While moshing, the concert-goers relinquish control through pushing, leaning and shoving one another following the movement and flow of the group. It reminds me of a hyperactive and harmoniously dissonant murmuration of birds or schools of fish.These temporary all ages show-spaces with their shitty PAs became my church, before and after I dropped out of the actual church at 16. And often, as I said, shows were literally in church basements around my mid-sized Midwestern city, as well as in more traditional venues, record shops, basements and cafes. Maybe that was an early noughties trend? I hope it still continues, the church providing a space that won’t be gentrified out of existence as many of the spaces that I used to go to have been.

Given the general lack of memory from my early years, the images of these shows and spaces are hilariously vivid. Drinking in the bathroom stalls with friends. The very satisfying and surreal sight of a singer screeching anti-establishment lyrics, often extremely anti-religious lyrics, in a drably painted canteen with a large framed printout photo of Jesus next to them. No gods, no masters. The church’s bulletin-board crowded with calendars of community activities and dates for the soup kitchen, placed alongside vacation bible school posters with Veggie Tales cartoons dressed in the clothes of biblical times (if you know, you know). Somehow these basements all looked the same: an interior of beige or pastel color textured wallpaper, with folding tables and brown or grey stackable chairs spread across a checkered linoleum floor. For a few upside-down hours the rooms would be cleared of the tables and chairs and swarmed with youth and the sprinkling of old timers in my city’s scene, dressed in black band t-shirts and looking strikingly unkempt against the 1970s-style sterile background.

It kept me going through the school week to look toward the next show. I could metabolize and accept the conditions of my life knowing that what felt like my actual life was waiting for me come the weekend. The shows would always be on Friday and Saturday nights, the basements cleared and cleaned for services on Sunday. Which in a way reflected a very Protestant relationship to the work week. There is the time for fun and then the time to be serious and they are definitely separate. No hoodies at church. Put on a dress.

I could express myself in a more aligned way in these spaces, my uniform of baggy clothes on my awkwardly tall frame of a “girl” in settled and unquestioned peace. I have an image that I hold very tenderly of the t-shirt I never changed out of my entire thirteenth year which read “Question Authority,” bought from Hot Topic with money I made from babysitting. Even when I played with femininity as an older teen, punk shows were a space where I could do it my way, rather than the dominant idea of what that was supposed to look like. I was not one of the cool or charismatic characters in my scene. I was very shy, searching for belonging as young people do, but I found a vast and lasting connection through the music. It became a healthier space for my obsessive brain to rest in, listening to a song over and over to memorize the lyrics. My friend and I burning one another CDs we would rip from the library or download. Dialing into my family’s internet for hours to read about bands, my family members yelling at me to get off so they could use the phone line.

In retrospect the conditions were far from perfect. The guy that ran the record label we followed religiously got called out for sexual violence a few years ago: he promptly shut down the label and moved to another state. As I was told what happened by an old friend, my stomach dropped, but my rational mind wasn’t that surprised as I mentally flipped through his dating history with much younger women and femmes. It made me sad as it tore apart the community around that label and its specific genre of folk punk. The scenes I moved through also were all incredibly white, and I know resulted in harm and discomfort for those who weren’t. The pit could get violent, depending on context or venue it could be very intimidating to mosh, especially for smaller people and women/femmes.

2

The history of mosh pits is a violent one and also one of sexual and physical assault. I’m not attempting to gloss that over in this writing. However, beyond the occasional bloody nose or inability to catch a stage dive by the crowd, I didn’t experience this kind of harm first hand in the spaces I moved in. I want, however, to acknowledge the pain of this reality and that, because of this, most pits could not be the space of freedom for everyone that I personally found them to be.As imperfect as it was, it was in this place that I was slowly politicized. Picking up ideas and building a new foundation of thought. Learning about anarchism through lyrics, zines and action. Learning about the genocide of the indigenous people of the land where I was born. How Turtle Island was colonized.

3

Turtle Island is the indigenous name of the land that was renamed by colonists North and Central America. The name comes from various Indigenous oral histories that tell stories of a turtle that holds the world on its back.4

Abbreviation of Counter Intelligence Program (1956 – 71). A series of covert and illegal projects actively conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, murdering and disrupting domestic political organizations affiliated with the black power movement, feminism, communism, anti-war organizing etc.In reflection, all these ideas were precious but, for me, the embodied power of these spaces lay in the fact that it was a group of people that moved together. That in unison, the ritual of moshing and experiencing music through the body gave me a way into myself and a way out the norms I was expected to conform to, and this was positively reflected back to me in others doing the same thing. Or maybe that’s just how I’m narrativizing it now, looking backward in the recounting. Attempting to understand my formation through what Susan Stryker calls the “historicity of identity”, which she describes as the contingency of oneself in the context in which one becomes a self.

I cannot separate my becoming a self from dance. There are multiple formative chapters, but the self-awareness of the importance of dance didn’t arrive in my story until I was twenty-three years old. This is when I found my way to improvisational and contemporary dance classes and jams. It began during a burn-out, a friend dragging me along to a $5 community dance class held in an old church (the theme continues) because she could tell I was emotionally low and numb and needed some kind of positive input. It worked. I mean it didn’t cure whatever was going on with me, but I kept going. Finding a space for dance that was about expressing feeling, curiosity and desire awoke me to the possibility of a relationship to the body which was centered around sensation. I remember my first class, the teacher asking us to move from a strong impulse in the body, so I focused on my chest. As usual it was tight with anxiety and tension but, for the first time in my life, I approached this space in my body without frustration, but instead by asking it what it wanted. I tentatively listened and began to move.

This moment was shaping. It began to teach me the lesson that I didn’t have to have a punitive relationship with myself, that I could at least be curious. It gave me another option to encounter pain and tension: sit with it and listen, rather than avoid and distract or control. As I dove deeper into dance and somatics throughout my twenties, I encountered various body nerds and dance geeks and movement witches and trained freaks and improvisers who offered countless thoughts and alternative approaches towards this thing we call body, self and mind, or the soma.

5

I use soma here in reference to somatics. The soma is the first person perception of the self through our proprioceptive senses, i.e., the body perceived from within.During this time a teacher and fellow movement witch, Maria F. Scaroni, introduced us to a practice of hers to use repetition as a technology of ecstasy. She invited us to shake for a long time, maybe an hour or so. I can’t fully remember, but it felt like a long time. That experience brought me to a feeling of interconnectedness in the body, like my edges were buzzing and dissolving. I found the sensation spiritual as it revealed a truth of my beings’ relationality to the others in the room, the city, and the planet, through a feeling in the body. I left my head -- it was a truth-thought felt throughout my being. I realized later that it was a very familiar state to me. It was one I had had many times before in the mosh pit, which now I can see was my first encounter with what could be called the ecstatic through movement.

Throughout nearly all of recorded human life on earth, certain forms and rituals around dance have functioned to be ecstatic in nature, resulting in states of trance and heightened emotions. From paintings made during the Stone Age depicting dancing, to the mosh pit or contemporary club, dance has been used because it is a powerful technology, a means of feeling god(s) or spiritual experience or connection to the collective through the body, rather than only believing in its power with the mind. Ancient Greeks would partake in worship of Dionysus, the god of wine, in which female followers would seek a state of “ekstasis” which means “to get out of themselves,” through wild collective dance. They were trying to achieve a state of possession by the god. Sufi whirling in the 12th century was used, and is still practiced today, as a moving meditation to connect to Allah through symbolic imitation of planets revolving around the sun, resulting in trance-like states. In Santería, an African diasporic tradition which developed in Cuba in the 19th century, dance and drumming are used as an invitation for oricha, Yoruba deities, to possess and thus communicate with members of the group. For many queer people dancing amongst one another, whether in the club, a house, a squat, a bar or a field has been a place of ecstatic experience and becoming in a world that is hostile to our joy.

These examples are just a drop of water in the ocean of the varied ways humans have engaged and cultivated movement technology for culture and worship, as well as individual and collective understanding and connection. I began to get curious about the histories and lineages of dance as a means of spiritual experience, particularly in the lineages I am directly connected to, i.e. my various European ancestral descendants. In my search, I quickly realized, without much surprise, it would be a story of religious and state repression, using discipline as a means to curtail ecstatic expression’s transformational force. This repression took place through colonization, the stealing of land and culture from others, as well as being aimed at cutting off their own polytheistic roots. As well as exposing the strange paradox that is at the heart of Chrisitanity: a belief in the embodied and incarnate God – a God who becomes flesh through the birth of Christ – and the fact that the contemporary institution of Christianity instead promotes disembodiment and disincarnation.

Its necessary to state before we get too deep into it that I’m attempting to find the stories of Christian religious history which has led to shaping me. There are infinite contemporary expressions of Christianity around the world I have not experienced, many born out of violent colonial histories of forced conversion, the fugitive mixing of gods and practice, long standing Christian mysticism and/or the lasting impacts of early heretical movements, which have developed and held onto traditions of ecstatic expressions of song, dance and movement in worship. I want to demarcate this because, at least from the outside looking in, they’ve maintained a connection to aliveness that was not present in my experience.

Looking back is an attempt for me to understand where the sense of aliveness went

6

My friend who is jewish calls Christianity a death cult – obsessed with death and the afterlife while respect for the divinity for living on this earthly plane feels secondary. Where I see the death cult of Christianity in modernity is colonialism, and the european Church’s (both Catholic and Protestant) part in using conversion around the world as a veil for genocide, slavery, the destruction of cultures, and the forced removal of indigenous people from their land. The obsession with the afterlife and purifying souls was just one effective propaganda method for justifying these horrific actions.In Barbra Ehrenreich’s book Dancing in the Streets: a History of Collective Joy she gives a thorough and nuanced outline of the church’s relationship to ecstatic movement practice. I want us to move together, so I will attempt to summarize here what stood out to me about early Christianity and dance so we can stay connected.

A Short and Dirty History of Christianity and Dance

At its roots Christianity included dance in worship. Clement of Alexandria (150-216CE) told followers in an early Christian cult to dance initiation rites in rings around the altar. Early Christianity was built on collective life – eating with one another in groups and participating in ecstatic rituals, like dance or speaking in tongues. Jesus’s radical origin story as an anarchist figure preaching love and sharing was a ministry that attracted the marginalized, women, the poor, sexworkers and the sick. Once the Romans took over and adopted Christianity as the state religion, it became more regulated and given increasing hierarchical formality and the marginalized were again pushed out to the edges.

However, into the Middle Ages, churches still danced. Priests and archbishops were even known to join in the holiday dancing within the church building itself

7

Interestingly, until the later Middle Ages, spaces of worship did not have pews. The church was a more physically open space, lending itself to embodied possibilities.8

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy by conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, but that cases of repeat unrepentant heretics were handed over to the secular courts, which generally resulted in execution or life imprisonment.Dancing within the church and graveyard stopped in the 12th and 13th centuries when priests began to purge dance physically from within the church, relegating it to specific holidays, both secular and holy, for example carnival. This was a compromise to dissuade heretical movements from springing up in response to an outright ban on celebration which, of course, failed, as heretical movements still formed despite their efforts. The church wanted a monopoly over human access to the divine, not only as a means of controlling Christianity’s narrative, but also safeguarding the church’s increasing wealth and political power.

Carnival existed as a means of revelry and, I’m sure, a space of ecstatic experience, whether through dance or substance. This festivity would harken back to pagan ritual, and also be used as what Ehrenreich calls a “safety valve,” for the powers that be. A day a year where the elites would allow ordinary people a space and time to let loose, to burn political effigies, to play and to dance.

9

I lived in Berlin for five years and it reminds me of May 1st there, the police and the black bloc performing the same dance every year on the same day, windows boarded in anticipation of the familiar performance, the vans lined up, paving stones in hand.However, from the 16th through 19th centuries, state and church attempted to control, sanitize and shut down carnival, typically by not renewing the permit to host it. These bureaucratic controls leaked out onto saints’ days, holidays and other occasions for reverie and play. In the south of Europe, spaces of carnival have continued, some becoming more of a procession ritual and others holding fast to their original wildness.

10

Four years ago in Marseille, a friend and I were astounded as we accidentally went to an “illegal”, i.e. without a city permit, carnival procession. We found ourselves walking up and down the windy streets, everyone dressed in costumes and holding sticks topped with paper mache politicians, company logos and military paraphernalia. All ending up together in a dingy car-park around the biggest bonfire I’d ever seen – I swear it was as big as a house – where people were drinking, dancing, burning the paper mache effigies and singing together. The intense heat of the fire could be felt deep in the bones, harkening to an ancient time which felt right and familiar.This repression of carnival is intimately tied with the dissolution and loss of the commons for the people and the spatial segregation of class in urban space. It wasn’t only the church that feared carnival, the state was also in favor of sanitizing or exterminating it. One reason for this antagonism was that, in the 15th and 16th centuries, carnival began to be used as a distraction for rebellion, robbery (think Robin Hood) and challenges to the powers that be. Everyone was conveniently wearing masks and costumes anyway, thus it was the perfect concealment. The aesthetics and rituals of carnival leaking into radical politics can also be seen in larger revolts such as the French Revolution, when animals were dressed up as politicians, and people made music and danced in the streets.

11

Carnival aesthetics and practices can still be seen in contemporary street protest tactics and strategies. I’m thinking particularly of the performative theatrics of the anti-globalization movement in the 1990s, but there are countless examples available.When the Reformation happened and Protestantism arrived on the scene in the 16th century, dance, and collective celebration in general, would be under further threat. Lutheranism and Calvinism, the early strains of Protestantism, disdained excess, celebration, drinking, gambling, and dance. They were seen as sin and a distraction from God. Politically, Protestant foundations of thought supported many ideals central to the emergence of capitalism. The middle-classes learned to calculate, save and defer gratification and the lower classes were disciplined into factory work six days a week. Ehrenreich makes the really interesting point that:

Protestantism – especially in its ascetic, Calvinist form – played a major role in convincing large numbers of people not only that unremitting, disciplined labor was good for their soul, but that festivities were positively sinful, along with mere idleness. In part its appeal was probably similar to that of much evangelical Christianity today; it offered people the self-discipline demanded by a harsher economic order: Curb your drinking, learn to rise before the sun, work until dark and be grateful for whatever you’re paid.

Scientific and philosophical theory of the time followed in the church’s footsteps to create a well rounded culture pitted against embodiment. Religious oppression of dance coincided with 17th century Age of Enlightenment attitudes towards the body, relegating it to a machine that was in service to the mind.

Seeing folk dance across cultures keeps me rooted knowing that spirit has stayed, regardless if it has been severed from the spiritual by oppressive power. I think about the contra-dances I grew up going to, and now the ceilidhs I’ve attended in the last three years living in Scotland. I’ve been grateful to experience the collective joy that erupts in these community dances, which I can feel through my body harkens back to something ancient, land based and important; even if that’s simply the connection of sweating together in unison on a cold winter night to experience being alive.

What I can tell from looking into all of this is that through the rise of state power and control of the Catholic and then Protestant church, dance in much of Europe was mitigated to being viewed as purely sociocultural, or given specific steps and technique and then raised to a “high” art form. It also became clear that the secularization of dance is also a story about class. Courts began to use dance as entertainment, developing concert dance such as ballet in the 15th century. While there is nothing wrong with form and training, I’m curious as to whether it lessens the availability of reaching ecstatic states, as a necessary part of the experience is the loss of control, which helps to move awareness from the mind into the body. Or this is how I’ve felt its power. Maybe it’s simply intentionality and the knowing, whether from self-experience or teachings or cultural context, that it’s possible to spiritually connect through dance. I know it can happen for individuals in folk dances, and even ballet, just as it does for some in the club, as almost anything can be devotional if there is intention behind it, but the relegation of dance into the purely social, and purely secular, is a site of mourning for me. So I ask, digging into what might have been and still could be:

What spiritual dances did my long-ago ancestors practice which have been lost or were relegated to the underground?

Though I don’t know what was lost, I do know where some rigidity was cultivated in its wake. My great grandmother was an active member in the German Mennonite Brethren Church, which originated in Germany, and whose congregation emigrated to the states due to religious persecution in 1719. My grandmother and mother speak very highly of her kindness, and I was named after her when I was born. Although she died when I was six and it’s a name I don’t use anymore, I still feel some kind of intimate connection to her. She was the child of German immigrants who arrived in Louisville, Kentucky in the early 20th century. Her family attended the church there as the service was held in German and her parents didn’t speak English. It was a fairly strict denomination of Protestant Christianity: there was an abstinence framework and they were not allowed to gamble, drink or dance, much like Calvinism’s original doctrine. My grandmother did not raise my mother in that church, nor her with me. I was raised in two different Protestant churches during my youth, and was actively engaged in those communities until I decided to stop going as a teenager.

I think about this generational relation to restriction through Protestantism and compare it to my mother’s father’s side of the family that has historically (and presently) struggled with addiction, with many relatives dying from alcohol-related illnesses. Restriction on one side and excess on the other matriarchally. This pendulum of being would become my way of coping, swinging between control and chaos, excess and restriction, lost to myself in this whiplash until my late twenties. Operating under a functional facade while being scared of almost everything, especially my own emotions.

It's important to mention here that my first expression of restriction came in the form of a childhood eating disorder which continued in different forms until three years ago when I sought recovery. It began when I was quite young. Food was there as a means to control my emotional states, a way to numb myself. It was the only tool for emotional regulation I had access to as a young person. Now I can see that with compassion, but until very recently it was a huge source of shame in my life and something I kept hidden, even from those I was in close relation to. When I think about it, this logic of rigidity fits well within the conception of a judgemental God.

In attempting to relate to my great-grandmother, I try to imagine life with the religious restrictions she accepted. I have been sober from alcohol for a while now, which has been hugely beneficial to my life, and I don’t gamble, so in these particular ways I can relate to her existence on a daily level. But I can’t imagine a life without dancing. Even when I’ve been in bed, sick as a dog with a flare-up of my chronic illness, I still, even in the most subtle ways, moved. I find joy watching others dance. I dance often in my mind when I’m bored, imagining what I’d like my body to do, how I’d move to a particular sound, what movement the music evokes and calls the body to make.

When I think about that impulse to dance being seen and metabolized as sin I get unbelievably sad. I think about that being carried generationally in the body through my matriarchal line, and what it means, especially in my body of white settler lineage born on colonized land.

12