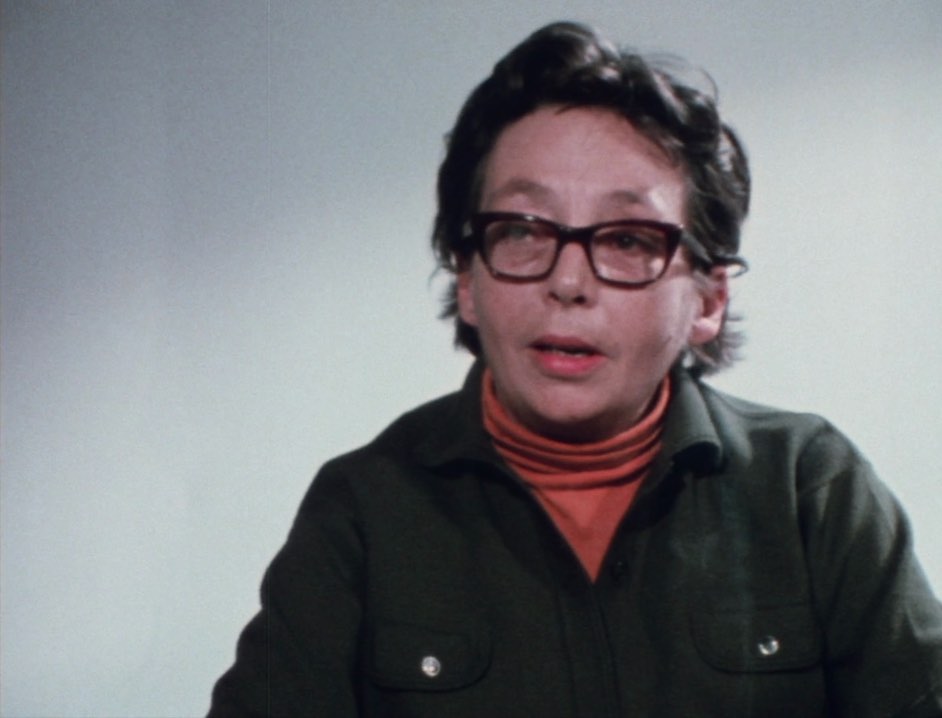

Lolo Pigalle Strip-teaseuse, Dim Dam Dom. Courtesy of l'Institut National de l'Audiovisuel (INA)

“A temperate insurgency laces the interviews Duras conducted for Dim Dam Dom, a magazine-style television show that ran from 1965 until 1970. Produced by Daisy de Galard, an editor at Elle, and broadcast on Sundays (“dimanche”), the programme was aimed at women (“les dames”) though it was hoped some men (“des hommes”) might find it interesting, too. And they did: Dim Dam Dom quickly gathered a cultish following for the promiscuity of its content (fashion, music, politics, interior design, cookery) and for the novelty of its format (de Galard gave the camera over to voguish, experimental filmmakers to create its playful cinematic segments). Agnès Varda and Claude Lanzmann were regular contributors, while Duras became the show’s popular correspondent. She interviewed celebrities but also ordinary people, including a seven-year-old boy, a stripper and a Trotskyist sixth-former (who now, in his sixties, is a friend of Macron).

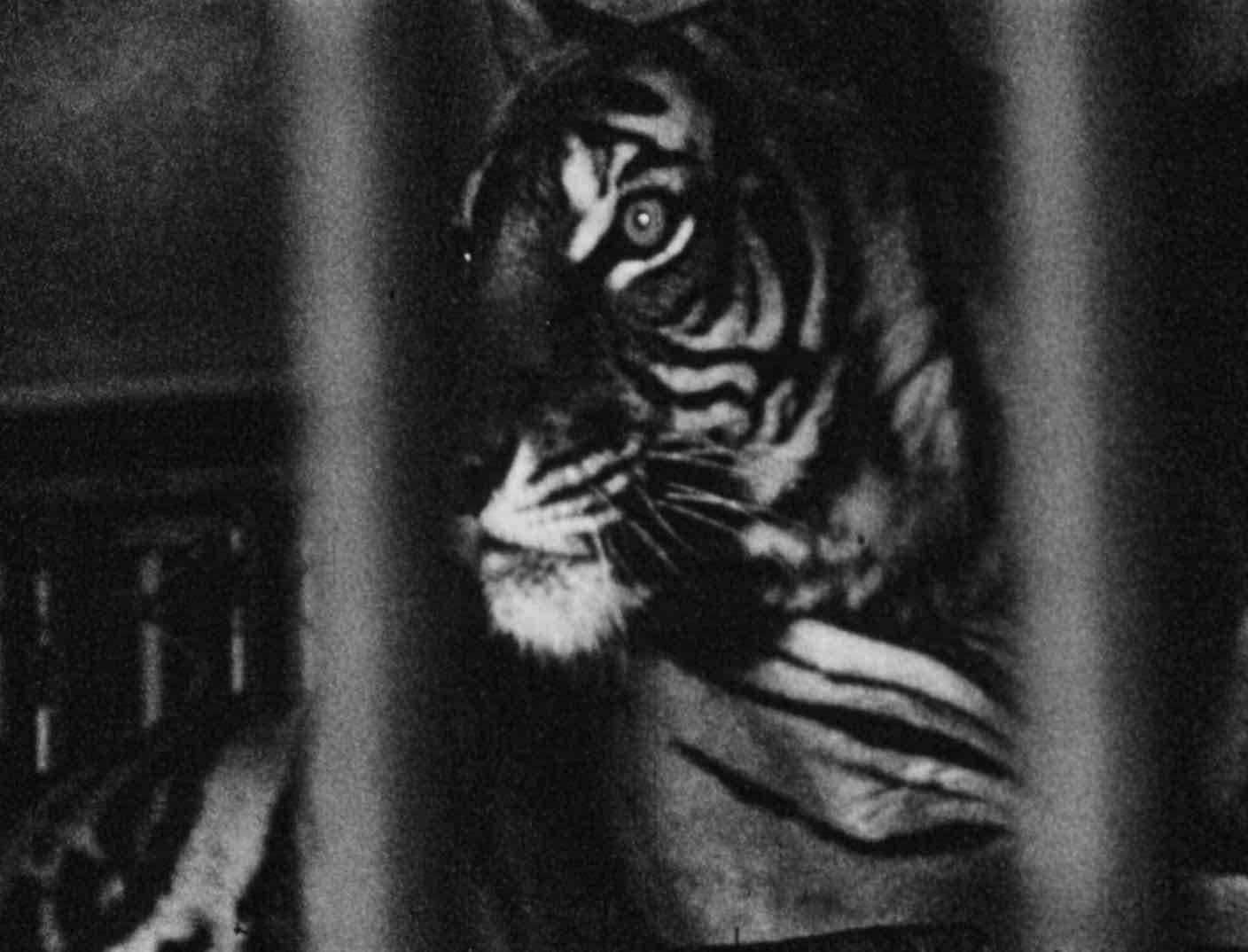

In an episode from 1966, entitled Marguerite Duras chez les fauves, Duras interviews a big-cat keeper at a Parisian zoo. The 16-minute segment opens with an incantatory monologue in which she muses about the animals: “Born in Paris. Their youth, here. Love and death, here. In Vincennes.” It would almost be funny – a parody of Durassian gloom and cadence – if the accompanying images weren’t equally melancholic: the lions pacing in their cage, the bars casting shadows over their fur (these images would later appear on a television screen in La Musica, her first feature, co-directed with Paul Seban whom she’d met through Dim Dam Dom). The episode is filmed with the dismembering intensity of surrealist photography and the light is so sparse that at moments we see little more than the brilliant flash of a black panther’s fang. Duras is appalled, convinced the animals are unhappy, and the film concludes with an abstract inversion: the camera now paces back and forth, agitated, tracking the zookeepers at work from inside the enclosure. With this sudden surfeit of pathos, the sharp edges of torment, yearning and exclusion that cut through all of Duras’s work are thrown into relief.

Outrage imprints itself quite forcibly on the episode entitled Marguerite Duras à la petite Roquette (1967) in which Duras meets France’s only prison governess. Duras asks her if she ever thinks about setting the prisoners free. “Are there suicides?” “What are the punishments?” The atmosphere is taut. The governess turns a letter opener over in her manicured hands, somewhat menacingly. She refuses to give herself over to Duras, who bristles at the evasions. They talk over one another until the governess brings the interview to an abrupt close – “I’m proud of what I do.” That we never see the women prisoners, only their empty cells, hardly matters: Duras has spoken on their behalf.

In Lolo Pigalle, a young stripper, Duras encounters a more affecting subject. The camera, wedged between the eaves of an attic apartment, tracks Pigalle’s movements as Duras narrates her biography. Many of its details resemble Duras’s own: Pigalle grew up in poverty with a mother who struggled to mother; decisions had to be made so that she and her siblings could survive. Pigalle doesn’t love her job, but she takes it seriously: we watch her perform in a gold lamé dress, moving artfully, her face is captivating, like a Nouvelle Vague heroine. Duras takes Pigalle seriously too, listening attentively as she explains the nature of sex work (it is work, she thinks: the cabaret is the same as “an office”) and what stripping reveals about desire (“a good face is more important than a beautiful body”). If there is a despair to stripping, Pigalle says it is because of the working conditions, the way it leaves so little time for being one’s “true self”. The scene ripples with feeling yet stops short of patronising sentimentality. In Pigalle, Duras finds what she was always looking for: the melodrama of everyday anguish.”

Extracts from Lili Owen Rowlands’ essay Marguerite Duras on Television, first published on Another Screen.

The programme will be introduced by writer and academic Lili Owen Rowlands.

In an episode from 1966, entitled Marguerite Duras chez les fauves, Duras interviews a big-cat keeper at a Parisian zoo. The 16-minute segment opens with an incantatory monologue in which she muses about the animals: “Born in Paris. Their youth, here. Love and death, here. In Vincennes.” It would almost be funny – a parody of Durassian gloom and cadence – if the accompanying images weren’t equally melancholic: the lions pacing in their cage, the bars casting shadows over their fur (these images would later appear on a television screen in La Musica, her first feature, co-directed with Paul Seban whom she’d met through Dim Dam Dom). The episode is filmed with the dismembering intensity of surrealist photography and the light is so sparse that at moments we see little more than the brilliant flash of a black panther’s fang. Duras is appalled, convinced the animals are unhappy, and the film concludes with an abstract inversion: the camera now paces back and forth, agitated, tracking the zookeepers at work from inside the enclosure. With this sudden surfeit of pathos, the sharp edges of torment, yearning and exclusion that cut through all of Duras’s work are thrown into relief.

Outrage imprints itself quite forcibly on the episode entitled Marguerite Duras à la petite Roquette (1967) in which Duras meets France’s only prison governess. Duras asks her if she ever thinks about setting the prisoners free. “Are there suicides?” “What are the punishments?” The atmosphere is taut. The governess turns a letter opener over in her manicured hands, somewhat menacingly. She refuses to give herself over to Duras, who bristles at the evasions. They talk over one another until the governess brings the interview to an abrupt close – “I’m proud of what I do.” That we never see the women prisoners, only their empty cells, hardly matters: Duras has spoken on their behalf.

In Lolo Pigalle, a young stripper, Duras encounters a more affecting subject. The camera, wedged between the eaves of an attic apartment, tracks Pigalle’s movements as Duras narrates her biography. Many of its details resemble Duras’s own: Pigalle grew up in poverty with a mother who struggled to mother; decisions had to be made so that she and her siblings could survive. Pigalle doesn’t love her job, but she takes it seriously: we watch her perform in a gold lamé dress, moving artfully, her face is captivating, like a Nouvelle Vague heroine. Duras takes Pigalle seriously too, listening attentively as she explains the nature of sex work (it is work, she thinks: the cabaret is the same as “an office”) and what stripping reveals about desire (“a good face is more important than a beautiful body”). If there is a despair to stripping, Pigalle says it is because of the working conditions, the way it leaves so little time for being one’s “true self”. The scene ripples with feeling yet stops short of patronising sentimentality. In Pigalle, Duras finds what she was always looking for: the melodrama of everyday anguish.”

Extracts from Lili Owen Rowlands’ essay Marguerite Duras on Television, first published on Another Screen.

The programme will be introduced by writer and academic Lili Owen Rowlands.

Marguerite Duras and Stripper Lolo Pigalle, (Lolo Pigalle Strip-teaseuse), 1965

Marguerite Duras and Little François (Marguerite Duras et le petit François), 1965

Marguerite Duras in the Lions' Den (Marguerite Duras chez les fauves), 1966

Marguerite Duras and the Prison Governess (Marguerite Duras à la petite Roquette), 1967

Marguerite Duras and the '68ers (Les lycéens ont la parole), 1968

Marguerite Duras and Little François (Marguerite Duras et le petit François), 1965

Marguerite Duras in the Lions' Den (Marguerite Duras chez les fauves), 1966

Marguerite Duras and the Prison Governess (Marguerite Duras à la petite Roquette), 1967

Marguerite Duras and the '68ers (Les lycéens ont la parole), 1968

02:30 pm

Sat, 20 Jul 2024

Cinema 1

Ticket information

- All tickets that do not require ID (full price, disabled, income support) can be printed at home or stored in email

- For aged-based concession tickets (under 25, student) please bring relevant ID to collect at the front desk before the event.

Access information

Cinema 1

- Both our Cinemas have step free access from The Mall and are accessible by ramp

- We have 1 wheelchair allocated space with a seat for a companion

- All seats are hard back, have a crushed velvet feel and they do not recline

- These are our seat size dimensions: W 42 x D 45 x H 52

- Arm rest either side of the seat dimensions: L 27 x W 7 x H 20

for the following requirements:

- We have unassigned seating. If you require a specific seat, please reserve this in advance

- Free for visitors where ticket prices are a barrier, please email

Members+ and all Patrons gain free entry to all cinema screenings, exhibitions, talks, and more.

Join today as a Member+ for £25/month.

no. 236848.